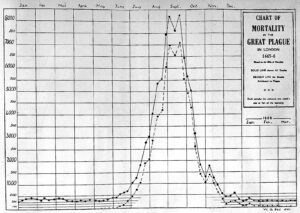

Mortality rates in London during the great plague of 1665/6, showing a typical pattern for plaque epidemics, i.e. the outbreak settling during the winter months (see below or click image for source and acknowledgements etc., ref. Image 1).

Amazingly The Great Plague of 1665/6 passed Newmarket by. However, an earlier notable big plague outbreak did hit the town badly, the 1625 epidemic. Plague broke out at Newmarket in the summer of 1625, taking hold until it died down in the early winter, mirroring the pattern in London that same year. In fact plague typically tended to die down in the winter months (see the chart on the right for the pattern in London during the 1665/6 outbreak). This disease had ‘plagued’ Europe since the Black Death of the 14th century, in which a very likely early local medic named Alexander de Ixnyng died. Smaller outbreaks were common until the 18th century, but The Great Plague of 1665/6 was the last big plague epidemic in England.

The population of Newmarket in 1625 has been estimated at perhaps 400-500 people – remarkably small, about the number of people in a typical street today! In fact plague is thought to have been one of the factors that kept the European population low for centuries. The 1625 experience in Newmarket is a good example of that. Over 100 people died between the start and end of the plague period recorded in the local burial records (so 20-25% of the population). That’s a typical death rate for plague. During the Black Death of 1348 it was even worse; it’s estimated that the population of Britain halved from 4 million to 2 million then (again an interestingly low population level to start with).

Plague traditionally is thought to have been caused by the bacteria Yersinia pestis, which is carried by rodents.* Many rodents are not necessarily harmed by this. Fleas bite the rodents and become infected themselves. The fleas can then bite humans and the bacteria crosses into the body at that point. Unlike many other rodents, rats do become sick when they contract plague. It’s thought that when plague spreads to rats mixed in with a human population, the mass death of rats encourages the fleas onto human hosts, encouraging an epidemic.

Where the bacteria enters the skin a small pustule sometimes develops, but spread in the body can be so fast that sometimes this does not have time to happen. The bacteria travels from this initial entry point to nearby lymph nodes, which become swollen, inflamed and painful – perhaps to the size of an orange. These are called buboes, which is where the term ‘bubonic plague’ comes from – typically these are seen in the groin, axilla or neck. This is the most common manifestation of plague – the main diagnostic sign. About 60% of people with bubonic plague die within a week of this sign (without modern antibiotics). Typical symptoms aside from the buboes are fever, headache and perhaps confusion. Sometimes it spreads to the lungs and causes plague pneumonia, so called ‘pneumonic plague’. This causes a cough and other respiratory symptoms. With these symptoms plague can spread directly from one person to another without the aid of rats and fleas. Nearly 100% of people who catch this form of plague die. In some people the bacteria spread rapidly in the bloodstream throughout the body, causing so called septicaemic plague. Internal bleeding can cause such extensive bruising that the victim appears black – hence ‘the Black Death’.

A typical costume worn by 17th century medics to visit plague patients (see below or click image for source and acknowledgements etc., ref. Image 2).

The only known medics in town during the 1625 epidemic were Robert Greene and perhaps Nicholas Searle the barber-surgeon. What would they have done?! They certainly would have advised quarantine of households, since although it was not understood how plague spread, people did realise that it was ‘spread’ and that quarantine/isolation might help contain the spread at least. The medical elite in cities were notorious for giving such advice then following it – miles away! However, the likes of Robert Greene and Nicholas Searle would usually have stuck around and done what they thought best. Robert Greene at least, who was definitely both medical and surgical (see the pages on Robert Greene and also The history of medical treatments, training, qualifications and regulation), would have recommended various herbal formulations, likely made by himself, both as prevention and treatment. Both might have incised the buboes, which patients were keen to have done apparently.** Dressing of wounds would have followed. Blood-letting or fumigation of rooms were other contemporary measures that they might have employed. Also general cleanliness, sober healthy living and exercise were typical recommendations apparently – just like advice from a modern GP! And although they probably realised that much of what they could do would have limited (if any) effect, they would have learnt how much it can mean to people in such circumstances just to be there for them, as we all still discover today as jobbing generalists (or barbers?!).

It’s amazing such medics survived, but don’t forget 80% of people did, although their exposure must have been high. It’s unlikely immunity from previous exposure would have helped them, since immunity to plague does not last long. Even today those at risk of exposure require frequent vaccinations (e.g. people working in areas where Yersinia pestis is present in the wild rodent population).

* There has been some suggestion in recent years that either Yersinia pestis was not the cause of these historic plagues, or that it was spread by a different mechanism. This page may be updated further in due course.

** It’s thought that’s what Cynefrid was doing for Etheldreda, described on the page about The history of medical treatments, training, qualifications and regulation.

Note: see the Newmarket fever epidemic of 1643? as well.

Note also, it’s often said locally that Newmarket began when plague in Exning caused the population to move up the road to found Newmarket (local folklore I’d understood to be the case myself before starting this research). Apparently there is no evidence for that idea, which appears first to have been suggested in the 19th century. The evidence (or lack of it), and what really appears to have happened, is discussed in detail in the 1982 publication by Peter May in the ‘other sources consulted’ below. On this website there’s a summary of how New-market apparently really began in the opening paragraph of ‘Henry Veesys etc. – medical care before the 17th century’.

Image 1: Chart of Mortality, Great Plague in London, from the Wellcome Collection; image used under CC BY 4.0, reproduced with kind permission of the Wellcome Collection. [Note: click here for the source.]

Image 2: Medic wearing a 17th century plague protection costume, from the Wellcome Collection; image used under CC BY 4.0, reproduced with kind permission of the Wellcome Collection. [Note: click here for the source.]

Note: see comments regarding images and copyright © etc. on the Usage &c. page as well.

1625: ‘Newmarkett All Sts’ archdeacon’s transcript. Reference: J502/17, microfilm of archdeacon’s transcripts, (Suffolk County Record Office, Bury St Edmunds).

1625: ‘Newmarkett St Marys’ archdeacon’s transcript. Reference: J502/17, microfilm of archdeacon’s transcripts, (Suffolk County Record Office, Bury St Edmunds).

British History Online. Hospitals: St John the Evangelist, Cambridge. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/cambs/vol2/pp303-307 (accessed 28th February 2015).

Duin N, Sutcliffe J. A History of Medicine. London: Simon & Schuster Ltd.; 1992.

Kiple KF. The Cambridge historical dictionary of disease. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2003.

May P. Newmarket Medieval and Tudor. Published privately; 1982.

May P. The changing face of Newmarket 1600 – 1760. Peter May Publications; 1984.

Sloan AW. Plague in London under the early Stuarts. S. A. Medical Journal 1974; 27th April: 882-888.

The research notes of Peter May. Reference: HD1584, (Suffolk County Record Office, Bury St Edmunds).

Note: For published material referenced on this website see the ‘Acknowledgements for resources of published material’ section on the ‘Usage &c.’ page. The sources used for original unpublished documents are noted after each individual reference. Any census records are referenced directly to The National Archives, since images of these are so ubiquitous on microfilm and as digital images that they almost function like published works. Census records are covered by the ‘Open Government Licence’ as should be other such public records (see the ‘Copyright and related issues’ section on the ‘Usage &c.’ page for which references constitute public records, and any other copyright issues more generally such as fair dealing/use etc.).